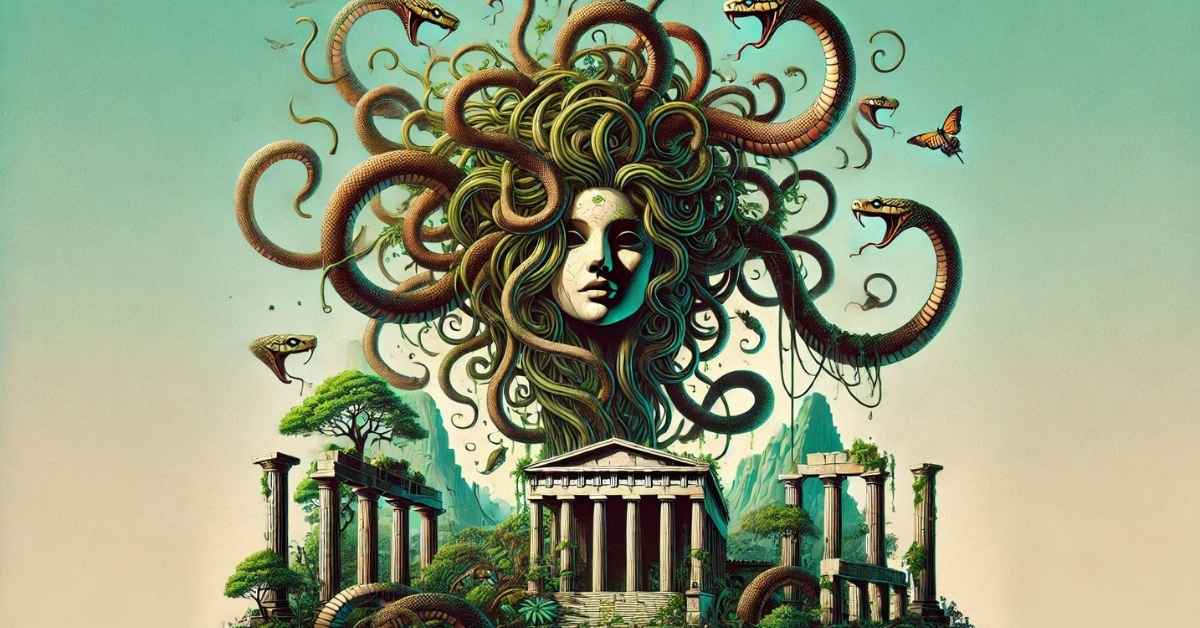

Medusa, recognized by her snake-laden hair and petrifying gaze, is arguably the most iconic figure in Greek mythology. But there’s so much more to her. For starters, the story you’ve seen in movies is only a small part of her complex history. Some say she was a woman turned into a monster, some claim she was born a mythical creature, while others see her only as a symbol.

By the end of this story, you’ll uncover the rich tapestry of mythology that surrounds Medusa and the origins of the Gorgon myth.

Origins of the Gorgon

While “Gorgon” is often used interchangeably with Medusa, the term traces back much further—possibly as far as 6,000 BC. Over millennia, the portrayal of these beings has undergone significant evolution. The name “Gorgon” derives from the ancient Greek word gorgos, meaning “grim” or “dreadful.”

Before the Gorgon became widely recognized as we know it today, there were other figures in Greek mythology that bore resemblances to this concept. One such example is the Erinyes, also known as the Furies, winged avengers tasked with punishing those who committed grave sins. Depictions of the Erinyes often included serpents wrapped around their bodies, suggesting that they may have been early representations of the Gorgons.

As Greek mythology evolved, new characters associated with the Gorgon narrative emerged. Notable figures include the Elder Gorgon, who some myths suggest might be Medusa’s father, and Gorgo, the daughter of the Titan Helios. These early Gorgons were distinct in appearance, often characterized by features such as beards, tusks, and curly hair. This depiction is quite different from the later, more familiar portrayal of Gorgons as snake-haired women.

Evolution of a Legend

By the 8th century BC, literature began shaping the Gorgon narrative, with Medusa taking center stage. Homer’s epics The Iliad and The Odyssey introduced the Gorgon as a formidable entity, her snake-covered head and stone-inducing stare becoming the stuff of legend. Interestingly, Homer described only a single Gorgon—Medusa.

Later, the Greek poet Hesiod expanded the myth in Theogony, a poetic account of the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods. In Theogony, Hesiod introduced the three Gorgon sisters: Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. Among them, Medusa stood out as the only mortal, though the nature of her mortality remains debated. Was she mortal only in her appearance, contrasting with her monstrous siblings, or was she mortal in her susceptibility to age and death?

By 490 BC, the poet Pindar offered a new perspective, describing Medusa as “fair-cheeked,” signaling a shift in her portrayal. Medusa’s duality as both beautiful and terrifying began to emerge, emphasizing not just her serpentine locks but also her captivating, petrifying gaze.

Poseidon, Athena, and the Betrayal

Perhaps the most poignant and debated version of Medusa’s tale comes from Metamorphoses, written by the Roman poet Ovid in the 1st century AD. Ovid dramatized myths, often casting the gods in a less-than-favorable light, and his portrayal of Medusa is no exception.

In Ovid’s narrative, Medusa was originally a beautiful maiden known for her lovely hair. She served as a priestess in the temple of Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom and warfare. Poseidon, the god of the sea, became infatuated with Medusa and pursued her. Despite her attempts to escape, Poseidon caught her in Athena’s temple.

Athena, upon discovering the desecration of her temple, was enraged. Instead of punishing Poseidon, she directed her wrath toward Medusa. As punishment, Athena transformed Medusa’s beautiful hair into a mass of writhing snakes, turning her into a Gorgon. From that point on, anyone who looked directly at Medusa would turn to stone.

This depiction of Athena acting out of jealousy or vengeance challenges her traditional image as a wise and righteous goddess.

Interpretations Through Time

Medusa’s story, especially as depicted by Ovid, has been interpreted in numerous ways, each revealing different facets of her character and the societal norms that shaped her tale.

In reaction to Ovid’s portrayal of Athena’s wrathful response, later adaptations sought to recast Athena in a more compassionate light. In these retellings, Athena’s transformation of Medusa was not a punishment but a protective measure. By making Medusa a Gorgon, Athena ensured that no man could ever harm her again, granting her a form that commanded respect and fear.

Another interpretation argues that Medusa’s transformation was a consequence of her own pride. By daring to equate her beauty with that of the gods, she incurred their anger. This aligns with the recurring theme in Greek mythology where hubris, or excessive pride, invites divine retribution.

Beyond her origin story, Medusa’s symbolic legacy is vast. Her visage was painted on protective shelters for women, and her severed head was used by Perseus to defeat the sea monster Cetus. Athena’s decision to feature Medusa’s head on her shield, the Aegis, cemented Medusa’s role as both a protective emblem and a symbol of formidable power.

Medusa’s Legacy

Medusa is not confined to a singular narrative or trait. She represents a spectrum of roles: victim, monster, maiden, protector, symbol of hope, and beacon of resilience. Her multifaceted nature makes her one of the most compelling figures in Greek mythology.

Medusa’s tale, rich in symbolism and interpretation, has transcended its ancient Greek roots to resonate in contemporary culture. Once feared for her monstrous appearance and her ability to petrify with a mere glance, she later evolved into a symbol of protection. Her terrifying face became a beacon of safety, appearing on women’s shelters and protective amulets called Gorgoneions, believed to ward off malevolent spirits.

Medusa as a Symbol of Female Empowerment

In recent years, Medusa has been embraced by feminist movements as a symbol of female empowerment. Her ability to paralyze men with her gaze is seen as a powerful metaphor for challenging patriarchal norms and asserting female strength.

Sigmund Freud’s Psychoanalytic Interpretation

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, offered a unique interpretation of the Medusa myth. He theorized that Medusa’s head symbolized a man’s deep-seated fear of emasculation, with the serpents in her hair representing male organs and her petrifying gaze metaphorizing male impotence.

Medusa in Contemporary Media

Contemporary films such as Clash of the Titans and Percy Jackson and the Olympians continue to introduce Medusa to new audiences, portraying her in diverse roles ranging from a fearsome foe to a tragic heroine. While these adaptations deviate from classical interpretations, they ensure that Medusa’s legacy remains vibrant and relevant.

Conclusion

Medusa’s enduring appeal is a testament to her complexity. She is not just a character from ancient mythology but a symbol that reflects the values, fears, and aspirations of different eras. As society evolves, so too does Medusa’s narrative. Her story reminds us that myths, no matter how ancient, can be reinterpreted to reflect contemporary values and beliefs.

What do you think of Medusa? Do you see her as a monster or a symbol of female empowerment? Let me know in the comments!